This they did at the evolutionary moment when the larynx descended deeper into the throat, thus making it possible to choke but also allowing well-articulated speech. To utter English, humans had first to acquire language.

Having convinced himself of English's pre-eminence, Mr. Anagramists couldn't rearrange ''World Cup team'' to get ''talcum powder.'' Palindromers couldn't write ''Sex at noon taxes.''

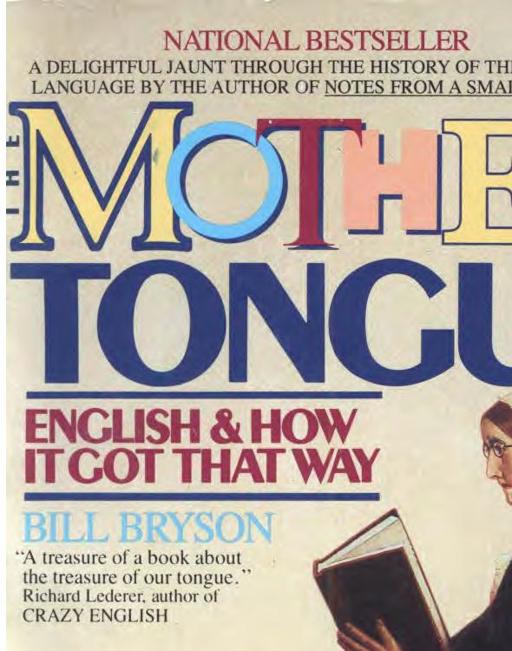

Without the sort of alphabet in which English is written, there could be ''no crossword puzzles, no games like Scrabble, no palindromes, no anagrams, no Morse Code.'' London Times puzzle-solvers would be deprived of clues like ''an important city in Czechoslovakia,'' meaning Oslo. More whimsically, he cites the sheer fun of English. The French call a self-service restaurant ''le self,'' and refer to a tuxedo or dinner jacket as ''un smoking.'' Meanwhile, the Ukrainians go to the barber to get a ''herkot.'' The Lithuanians go to the theater to see ''muving pikceris'' and the Japanese season their conversations ''with upatodatu expressions like gurama foto (glamour photo), haikurasu (high class), kyapitaru gein (capital gain) and rushawa (rush hour).'' ''Even in France, the most determinedly non-English-speaking nation in the world, the war against English encroachment has largely been lost,'' Mr. He cites the tendency of English to invade foreign cultures. Then again, ''there are now more students of English in China than there are people in the United States.'' He cites the prevalence of those who express themselves in English, there being, he estimates, 44 countries in which English is spoken as an official language, as against 27 for French and 20 for Spanish, although, he admits, there are over twice as many speakers of Mandarin Chinese, or Guoyo, (750 million) than there are of English (350 million). He cites the huge number of words available to the speaker of English, the flexibility of the language and the relative ease of spelling and pronunciation, at least compared with, say, Chinese or Welsh. Bryson's previously published books are A Dictionary of Troublesome Words and ''The Lost Continent: Travels in Small-Town America.'') How dare he call English the ''most important and successful language in the world''? His standards are not all that precise. So writes Bill Bryson, an American journalist now living in England, in his entertaining new book, ''The Mother Tongue: English and How It Got That Way.'' (Mr.

''It is a cherishable irony that a language that succeeded almost by stealth, treated for centuries as the inadequate and second-rate tongue of peasants, should one day become the most important and successful language in the world.''

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)